Introduction: A Camera That Waits

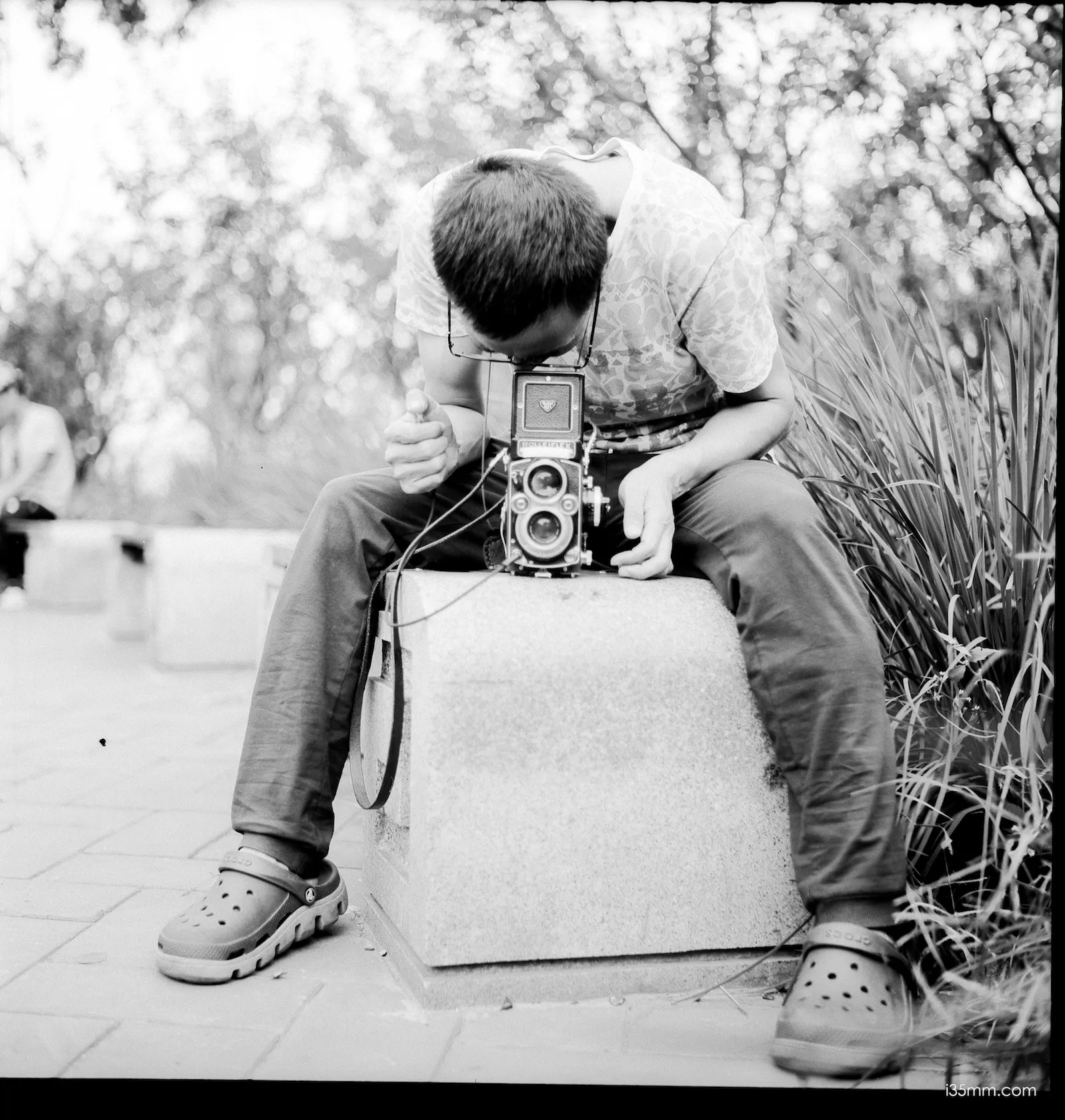

They say every Leica owner keeps a Rolleiflex at home, gathering dust like an old love letter. I’m no twin-lens fanatic, but I get it—there’s something about these square-eyed boxes that lingers. My Rolleiflex 3.5 MX-EVS isn’t the fanciest of its kind. It’s the last of the non-interchangeable focus screen models, a budget relic with no meter, picked up cheap from a forgotten shelf.

Design & Build: A Mechanical Poem

The MX-EVS sits heavy in your hands, a brick of German steel and glass from the early ’50s. It’s all manual, all mechanical—no bells, no whistles—just the way I like it, echoing the Leica M3’s stubborn simplicity. Early models wore white plastic like a shy debutante, but mine’s cloaked in black paint, chipped at the edges, whispering tales of a life before me. The Tessar lens, a 75mm f/3.5, stares up from its twin perch, unassuming yet precise. Rolleiflex moved to Zeiss and Schneider glass later, but this one? It’s raw, honest, built to last—like a typewriter that still clacks in a digital age.

Features: The Art of Less

This isn’t a camera that spoon-feeds you. No built-in meter means you’re on your own, guessing exposure like a drifter reading the sky. The film counter’s automatic, though—a small marvel that clicks with every frame of 120 film, a nod to German ingenuity. The waist-level viewfinder flips open like a secret hatch, revealing a world flipped left-to-right. It’s disorienting at first, a mirror to somewhere else, but that’s the charm—you’re not just shooting; you’re dreaming in reverse.

Performance: Street Shadows and Square Frames

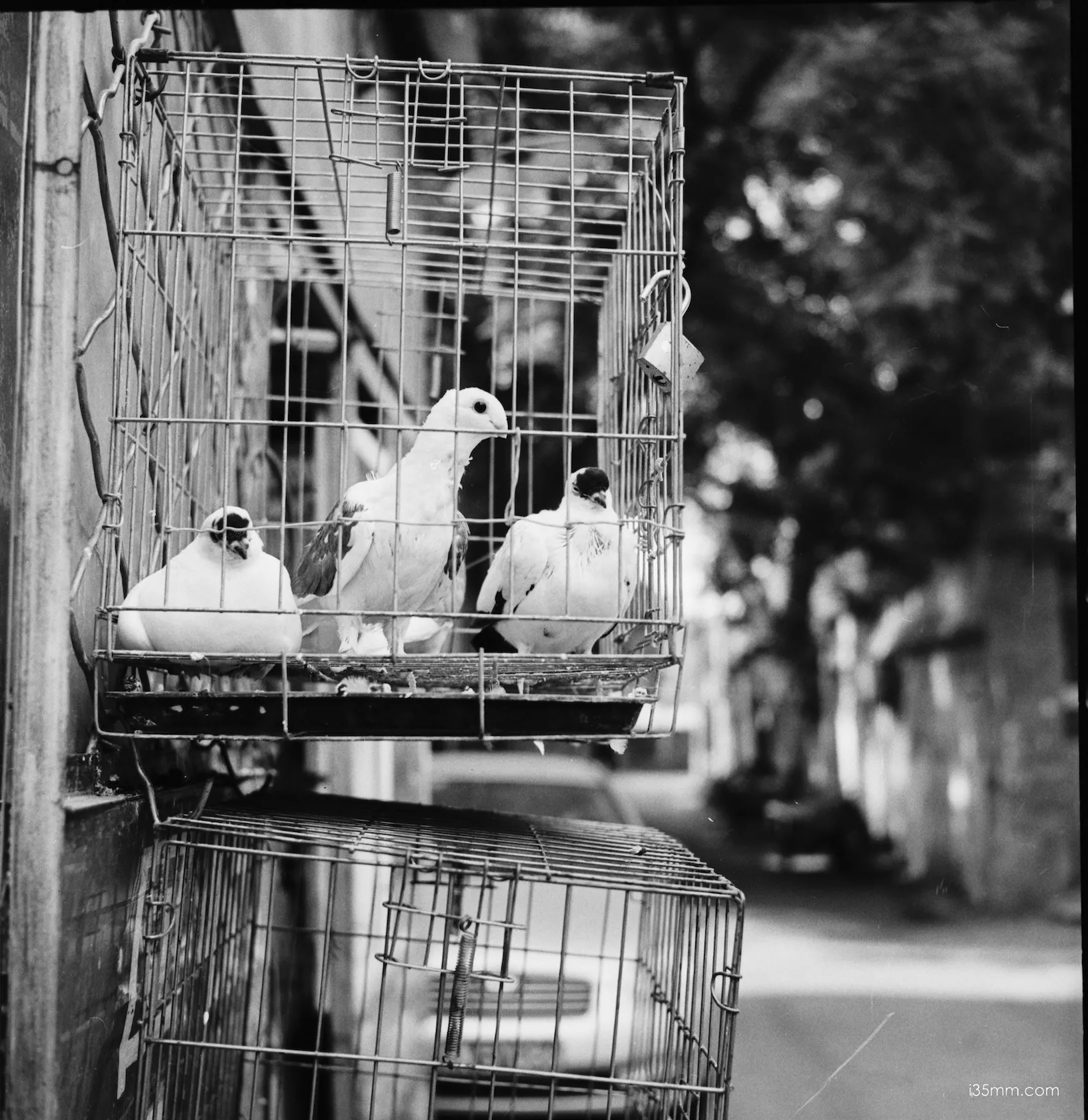

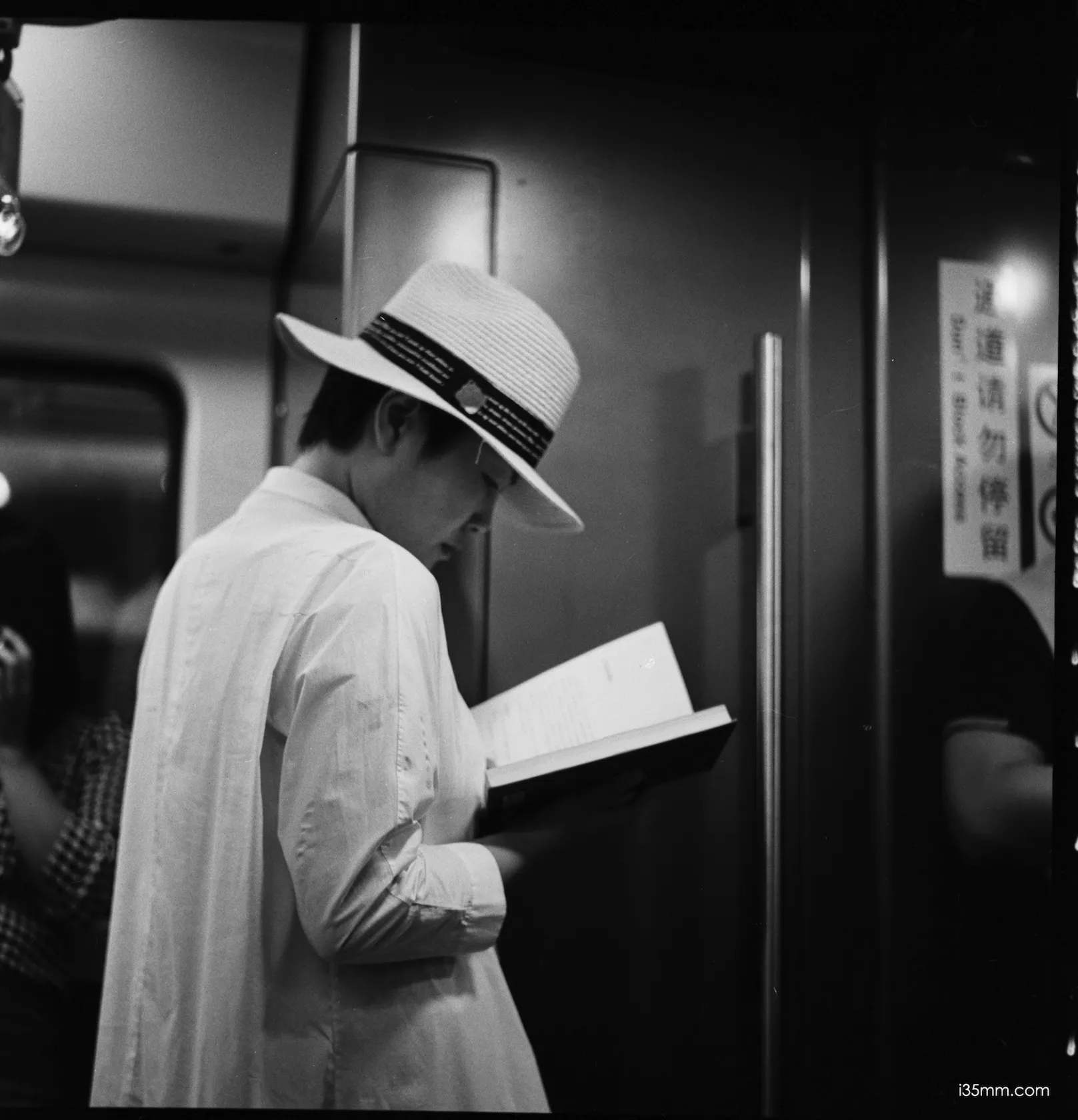

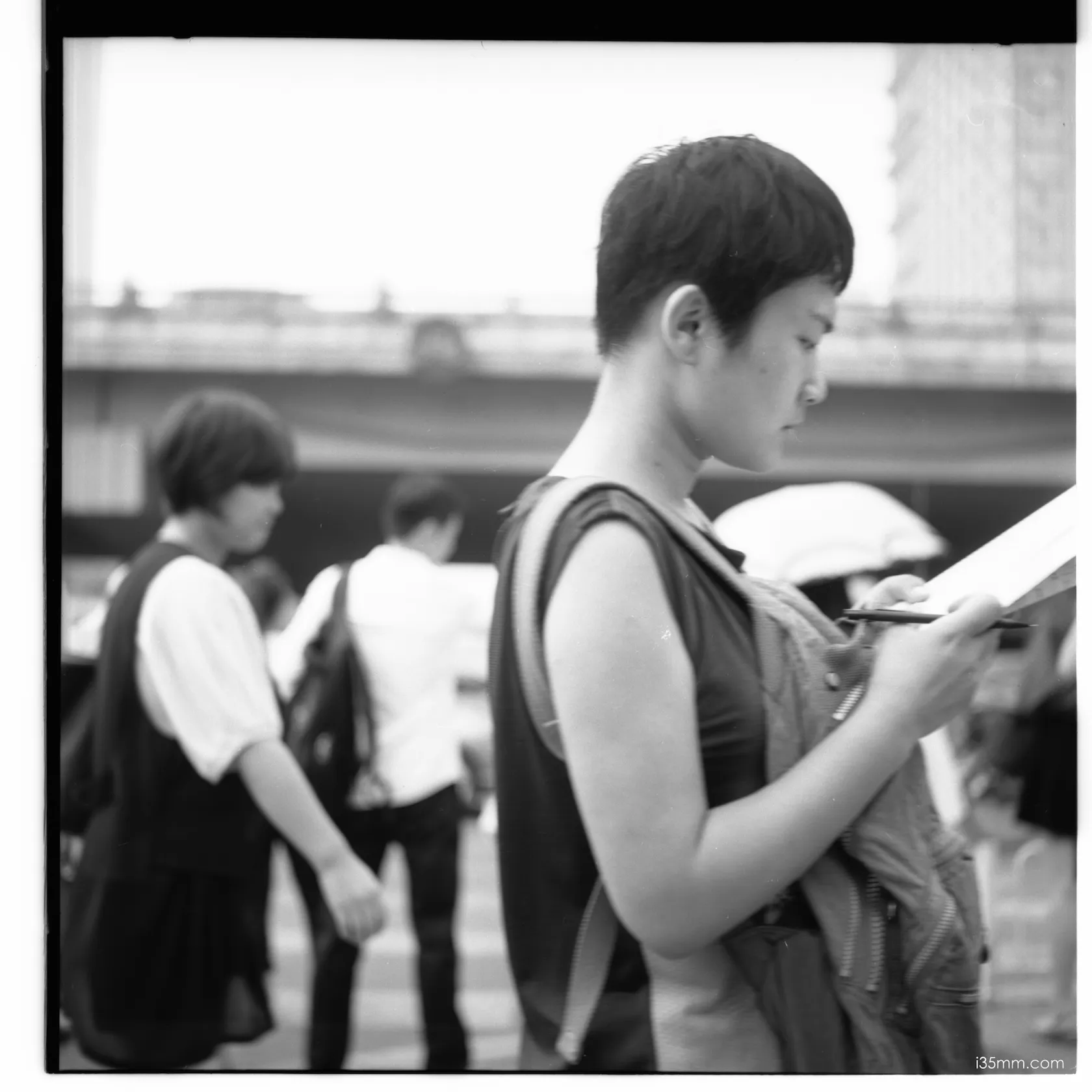

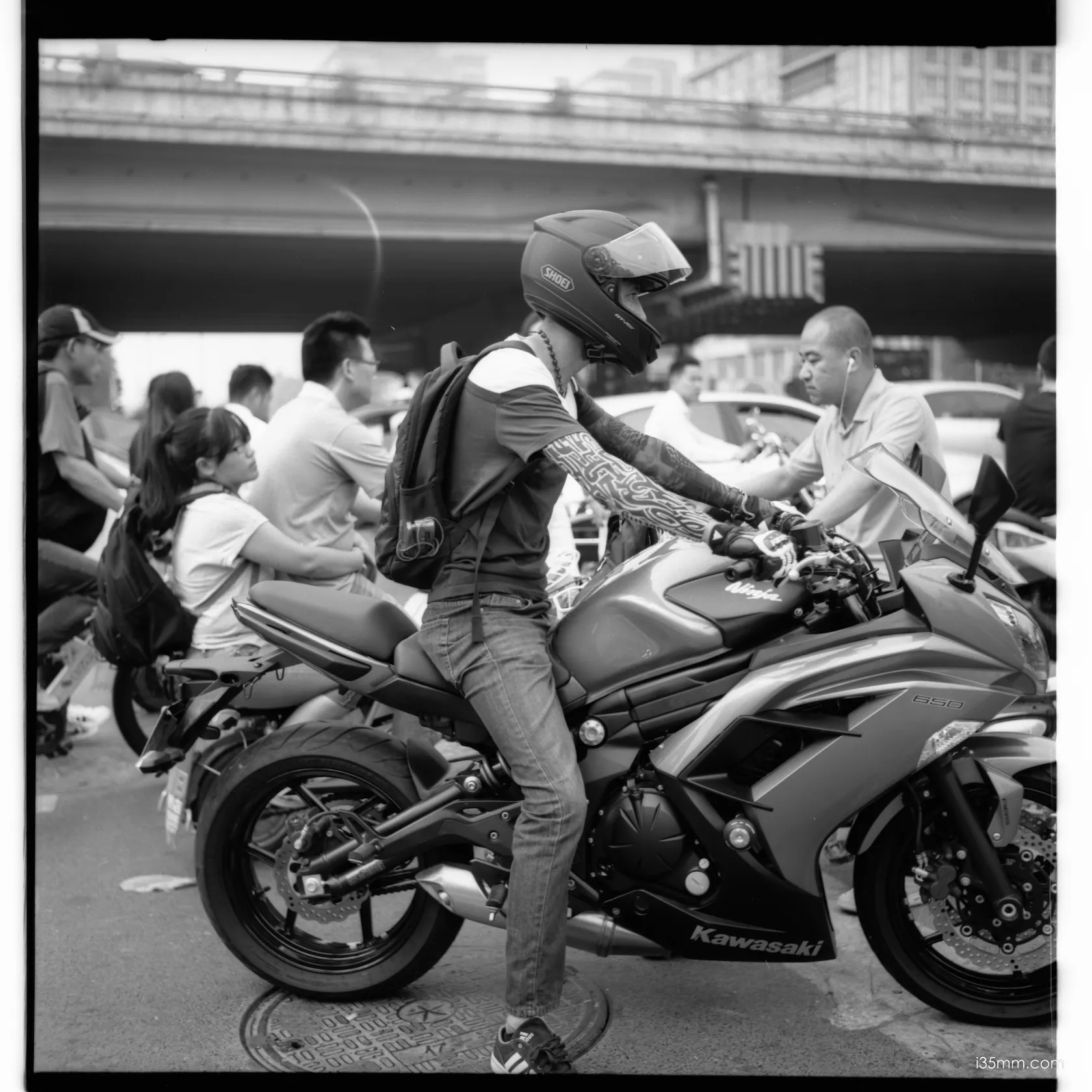

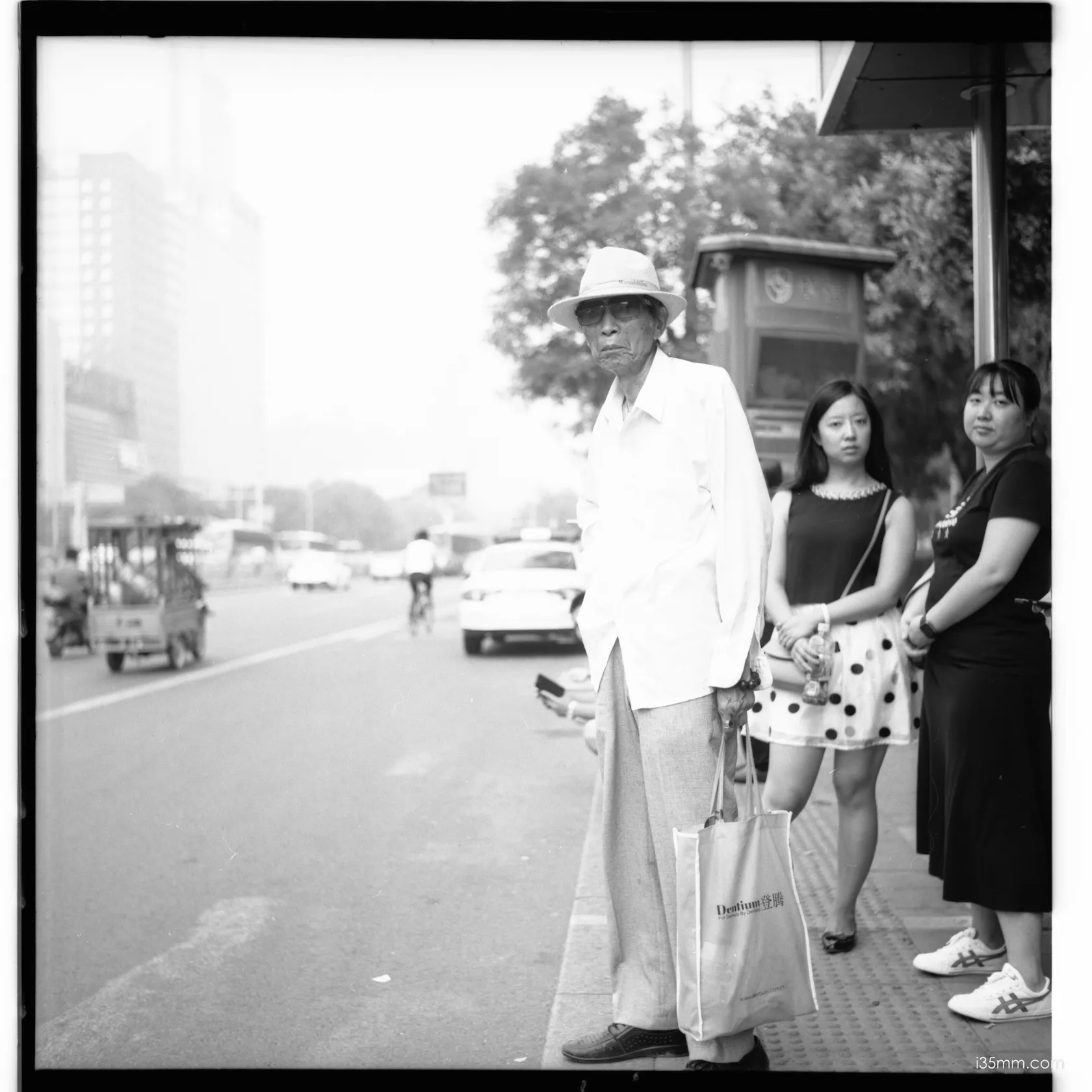

I took the MX-EVS to the streets, chasing echoes of Robert Doisneau and Vivian Maier—masters who saw poetry in the mundane through a Rolleiflex. There’s a story from the ’50s: Henri Cartier-Bresson praised the Leica’s agility in one paper, and the next day, Doisneau countered with the Rolleiflex’s knack for candid grace. I see why. Peering down into that glowing square, reality bends—left becomes right, and time slows. The Tessar lens paints shallow depth and creamy bokeh, turning strangers into soft-edged legends.

But 120 film threw me off. Coming from 135, my “sunny 16” guesses overexposed half my rolls—bright blurs instead of crisp tales. It’s four times the size of 35mm, a beast to scan but a gift in detail. Portraits shine here—square compositions frame faces like old photographs in a family album. Still, I’ve sidelined it lately; my impatience doesn’t match its rhythm.

Pros & Cons: A Love with Limits

Pros:

- Gorgeous square shots with dreamy bokeh—perfect for portraits.

- Built like a tank, a survivor from 1951.

- That flipped viewfinder—it’s a portal to another world.

Cons:

- No meter means exposure’s a gamble (and I’m a lousy card player).

- 120 film’s a learning curve—pricey and unforgiving.

- Slow to shoot; it’s a thinker, not a sprinter.

Conclusion: A Letter to the Past

The Rolleiflex 3.5 MX-EVS isn’t for everyone. It’s not sleek like a Leica or loud like a Nikon. It’s a quiet companion, a twin-lens ghost that asks you to pause, to feel the weight of each click. I’ve got a Chinese Orient 120—a Tessar knockoff—that mimics it well enough, and the world’s full of Rolleiflex copies. But this one’s mine, a worn treasure I’ll keep, even if it mostly guards my shelf now.

Wenders might say every photo is a letter to someone gone. With this camera, I’m writing to the streets—Doisneau’s Paris, Maier’s Chicago—hoping the light answers back. Pick up a Doisneau book, let it sink in, and maybe you’ll see why I can’t let this Rolleiflex go.

Tech Specs:

- Lens: 75mm f/3.5 Tessar (4 elements, 3 groups)

- Shutter: Compur-Rapid, 1s to 1/500s

- Film: 120 (12 shots per roll)

- Weight: ~900g